CONSTANTINE THE AFRICAN AND GERARD OF CREMONA

Scientific Envoys of Islamic Medicine to the West

Many people dream of being able to take part in some great scientific or cultural mission that advances the cause of humanity. Such was the charmed life of Constantine the African, also known by his Latinized name, Constantinus Africanus. Seeing that the European medical knowledge of his day was far behind that of his native Tunisia, where advanced treatises on medicine in Arabic were available, and studied, he decided to remedy this situation by bringing many of these Arabic medical treatises to Italy and translating them into Latin for the benefit of doctors and medical students throughout Europe. Constantine’s name and influence will always be connected with the famous medical school of Salerno, in southern Italy, due, in large measure, to the wealth of medical literature he brought with him and translated into Latin.

Constantine was born in 1017 in the Tunisian city of Kairouan, and studied medicine there, as well as in Baghdad. Constantine was an avid collector of medical books and treatises, and had also visited the city of Salerno in southern Italy, which was, in his day, the leading center of medical learning in Europe. Unfortunately, he saw that the overall level of medical learning in Salerno lagged far behind that of the Arab and Islamic world of his time. As fortune would have it, three years after his visit to Salerno, Constantine was accused of sorcery in Carthage, where he was living at the time, and was sent into exile. Recognizing this seeming misfortune as a golden opportunity to take his medical books and knowledge to Europe, he took his medical library with him on a ship bound for Salerno. His ship was wrecked, and some of his medical books were lost, but many more he was able to save.

Constantine was born in 1017 in the Tunisian city of Kairouan, and studied medicine there, as well as in Baghdad. Constantine was an avid collector of medical books and treatises, and had also visited the city of Salerno in southern Italy, which was, in his day, the leading center of medical learning in Europe. Unfortunately, he saw that the overall level of medical learning in Salerno lagged far behind that of the Arab and Islamic world of his time. As fortune would have it, three years after his visit to Salerno, Constantine was accused of sorcery in Carthage, where he was living at the time, and was sent into exile. Recognizing this seeming misfortune as a golden opportunity to take his medical books and knowledge to Europe, he took his medical library with him on a ship bound for Salerno. His ship was wrecked, and some of his medical books were lost, but many more he was able to save.

When Constantine arrived in Salerno, the Norman duke Robert de Guiscard had just wrested control of Salerno from the Byzantines, and before that, he had taken Sicily back from Muslim rule. Being somewhat at the portal or crossroads between the European and Islamic worlds, Salerno was a cultural and intellectual melting pot. Constantine had brought with him not only Arabic translations of classical Greek medical works by Hippocrates and Galen, but also more advanced medical treatises by Islamic physicians and medical scholars. In Salerno, Constantine became a professor of medicine, and his teaching skills soon began to attract widespread attention. A few years later, Constantine converted to Christianity and became a Benedictine monk, living out the last two decades of his life in the Monte Cassino monastery. Alfano, the archbishop of Salerno, who had considerable medical knowledge of his own, took a keen interest in Constanine’s linguistic abilities, and encouraged him to translate various popular medical texts from Arabic into Latin for the benefit of medical students.

Constantine’s Translation Work and Its Legacy

Constantine the African was definitely a pioneer in the importation, translation and sharing of medical literature and knowledge from the Islamic world to Christian Europe. And so, some commentators have even seen him and the intellectual ferment he unleashed as being an early forerunner of the Italian Renaissance. And others, like the prolific Italian scholar Gerard of Cremona, would continue where Constantine had left off in the translation of Islamic scientific and medical treatises into Latin and other European languages. Gerard would pursue his translation work in the following century in Toledo, Spain, which was another portal or gateway city between the Islamic world and Christian Europe. Together, these two scholars, Constantine and Gerard, played key roles in opening the floodgates of medical knowledge between the Muslim East and the Christian West.

Constantine was far more than a simple translator of medical literature from Arabic into Latin; he was also utilizing his pedagogic talents to adapt the information from the original Arabic treatises to fit them to a European audience. His overriding concern was how to present the Islamic medical knowledge in such a way as to be most relevant and accessible to his European students. Some accuse Constantine of being a plagiarist, but what they are forgetting is that the region of southern Italy, in which he was teaching, had recently been under Muslim domination, and his Christian audience didn’t want to be unduly reminded of their Muslim past. In about the same year that Constantine died, another scholar and physician would be born in Salerno who would also teach there, and have a distinguished place in the history of European medicine. This was Trotula, who distinguished herself not only being a physician and medical professor, but by being a woman as well – one of the first women in a field that was dominated almost exclusively by men. She produced a body of work called The Trotula.

Arabic Medical Treatises Translated and Adapted by Constantine the African

Perhaps the best known and most important and voluminous Arabic medical treatise that was translated by Constantine the African was what became known by its Latin name the Pantegni. This Latin word means, “The Whole (Medical) Art”, which pretty much sums up the essence of the original Arabic title: Kitab Kamil As-sin’a at Tibbiya, which was written before 977/978 by Ali ibn a-Abbas al-Majusti.

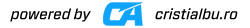

Other Arabic medical treatises translated by Constantine the African had Latin names such as: Chirurgia (Surgery), Prognostica (Prognostics), De Pulsibus (On the Pulse), De Instrumentis (On [Medical] Instruments), Practica ([Medical] Practice), De Stomachi et Intestinorum Infirmitatibus (On Infirmities of the Stomach and Intestines), Liber de Urina (Book on the Urine), and others. With the city of Salerno so blessed by the medical knowledge and literature bequeathed to it by the prodigious efforts of Constantine in the translation and adaptation of Arabic medical works for a Latin audience, it was only natural that, in the following century, Europe’s first medical university was opened in Salerno.

And so, the great medical legacy of Constantine the African lives on for all posterity, and it may be difficult to fathom exactly how much Western science and medicine owe to the efforts of this one man. He definitely started a trend, or “started the ball rolling”, so to speak, in the direction of the translation and importation of other vitally important Arabic medical texts into Europe, for the benefit, enlightenment and advancement of European science and medicine. And so, Constantine the African could be called not only the Muslim that Ignited the Renaissance, which may be a bit of a stretch chronologically speaking; he could definitely be called the Father of European Medicine. In business and entrepreneurship, there is a maxim: Find a need, then fill it. Constantine was simply following this principle, but on a higher humanitarian level than that of mere personal profit.

The Torch is Passed to Gerard of Cremona

After Constantine the African had passed away, his work and legacy were taken up by a prolific and remarkable scholar, translator and polymath by the name of Gerard of Cremona, whose Latin name was Gerardus Cremonensis. He was active about a century later than Constantine, and was one of the Toledo group of translators of Muslim scientific and medical literature. Gerard was born in Cremona, Italy in 1114, and died there in 1187. According to the Dominican friar Francisco Pipino, we learn that Gerard was drawn to study Arabic in Toledo propelled mainly by his great love of Ptolemy and astronomy. His proficiency in Arabic grew so great that not only did he translate the entirety of the Almagest into Latin, but all the works of Avicenna as well. According to friar Pipino, Gerard translated a total of some 76 medical and scientific works into Latin. Gerard of Cremona is also conflated by some authors with Gerard of Sabionetta, a scholar and translator with similarly wide ranging interests who lived and worked in the 13th century, but whether they were two distinct individuals or not remains unclear.

After Constantine the African had passed away, his work and legacy were taken up by a prolific and remarkable scholar, translator and polymath by the name of Gerard of Cremona, whose Latin name was Gerardus Cremonensis. He was active about a century later than Constantine, and was one of the Toledo group of translators of Muslim scientific and medical literature. Gerard was born in Cremona, Italy in 1114, and died there in 1187. According to the Dominican friar Francisco Pipino, we learn that Gerard was drawn to study Arabic in Toledo propelled mainly by his great love of Ptolemy and astronomy. His proficiency in Arabic grew so great that not only did he translate the entirety of the Almagest into Latin, but all the works of Avicenna as well. According to friar Pipino, Gerard translated a total of some 76 medical and scientific works into Latin. Gerard of Cremona is also conflated by some authors with Gerard of Sabionetta, a scholar and translator with similarly wide ranging interests who lived and worked in the 13th century, but whether they were two distinct individuals or not remains unclear.

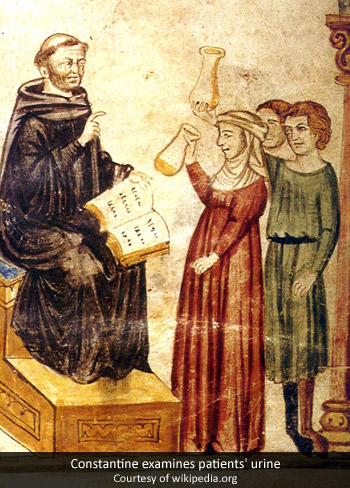

Out of the 76 or so works that Gerard translated from Arabic into Latin, no fewer than two dozen of them are devoted to medicine. Although some of these works were originally by classical Greek authors, the vast majority of these medical works were by the great masters of Islamic Medicine. These include seven works by Al-Razi, whose Latin name was Rhazes, including his two medical encyclopedia compilations: the Liber Al Mansoris and the Continens. Most notably, Gerard translated Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine into Latin, a book that went on to be the most influential textbook in European medical universities like Salerno throughout the medieval and Renaissance eras. Another notable medical work translated by Gerard was the Chirurgica (Surgery)of Albucasis (Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi). The sheer importance of all these great medical works to the advancement of European medicine can hardly be overestimated. Constantine the African was the pioneer or forefather of this great translation movement, but Gerard translated the monumental medical works of the great masters, Rhazes, Avicenna and Albucasis, which came from the full flowering or zenith of Islamic Medicine.

The translation of Muslim medical treatises by Gerard and Constantine introduced physicians and medical scholars in the West to the great advances made by Arab physicians in fields like surgery, materia medica and theoretical pharmacology. Gerard’s translation of the Great Arabic medical encyclopedias like Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine opened the eyes of medical scholars in the West to the fact that medicine was a rational science that could be studied logically and methodically, which had a sound foundation in philosophy and the natural order. In addition, the espousal of certain systems of classical Greek philosophy by these masters of Islamic Medicine, such as Avicenna’s orientation towards Aristotelian or Peripatetic philosophy, opened the eyes of Western Christendom to the light of reason and philosophy, an intellectual current which eventually led to Saint Thomas Aquinas’ development of Scholasticism, a system of philosophical theology that endeavored to achieve a perfect blending of faith and reason. This awakening of Western Christendom to the light of rational and humanitarian values led eventually to the Italian Renaissance.

Sources: www.academia.edu - www.newadvent.org